What is the role of faith in our current world?

‘Discord’ at Bridge Street Theatre encourages us to not be afraid of our neighbor’s beliefs

By Jeff Borak

Link to Original Article

CATSKILL, N.Y. – Writer and television executive producer Scott Carter readily acknowledges he knew very little about Thomas Jefferson, Charles Dickens or Count Leo Tolstoy when he decided to put them together in a locked room in an undefined afterlife space — perhaps limbo; perhaps purgatory.

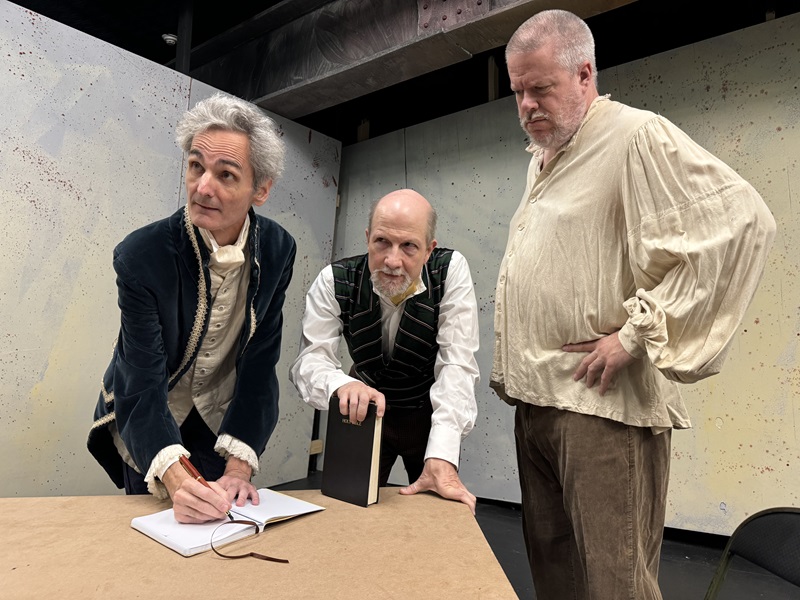

“We are adrift. In an ark,” Dickens says to his companions. “Three Jonahs in a whale’s belly. May God soon expel us,” Tolstoy replies in Carter’s “The Gospel According to Thomas Jefferson, Charles Dickens and Count Leo Tolstoy: Discord,” which begins a two-weekend run this weekend at Bridge Street Theatre in a production directed by Carmen Borgia and featuring Brian Linden as Jefferson, Jason Guy as Dickens and Zach Curtis as Tolstoy.

Carter will be at the theater Nov. 15, 16 and 17 for post-performance talkbacks with audiences.

“This will be the 12th production I will have seen,” Carter said by telephone from his office in Los Angeles, where the former executive producer and writer for 16 seasons of “Real Time With Bill Maher” lives and runs Efficiency Studios, a podcast and television production company.

“Discord” premiered at the Geffen Playhouse in Los Angeles in October 2014 and has since been produced in 26 cities in four countries. In the United States, “Discord” has been produced in Dallas, Philadelphia, Detroit, Tucson, Skokie, Ill., and in the Berkshires at Chester Theatre Company in 2015.

“Discord” had been in development long before its Los Angeles premiere. Carter credits a near-death experience on a Sunday morning in New York in June 1987 when the lifelong asthmatic, then struggling stand-up comedian, suffered an attack that very nearly claimed his life. He was released from the hospital six days later on what he describes as a “steamy Saturday afternoon.” He had a life changing epiphany that led him to make three promises to himself, to the universe — “first, anyone who wanted to speak to me about religion, I would listen,” he said. Second, if he was asked to read any spiritual literature, he would; third, if he was invited to attend any religious ceremony or occasion, he would, irrespective of his personal beliefs. His health improved as did his personal and professional life. And then, one night, he saw on television an episode of Bill Moyers’ “World of Ideas” on which Moyers discussed the Thomas Jefferson bible in which the great statesman and third President of the United States focuses on Jesus Christ as a moral philosopher.

“I got a copy of ‘The Jefferson Bible and was fascinated by the ideas about Jesus he picked and the ideas he discarded,” Carter said.

Carter’s intellect and imagination turned toward the notion of writing a play about Jefferson and his bible. Not long after he began writing, Carter stumbled across a book about Charles Dickens in a bookstore and discovered that the noted Victorian novelist also wrote a bible, “The Life of Our Lord,” for his children. Carter redirected his energies to include Dickens in his play, until he came across Stephen Mitchell’s “The Gospel According to Jesus” and discovered that Tolstoy had written a bible — “The Gospel in Brief.”

The notion that each of these three titans of literature and statesmanship had written bibles was irresistible.

“I had to tear up what I had written to include Tolstoy,” Carter said.

His dramatic conceit revolves around the efforts of the three men to come up with a commonly agreed upon gospel text. Carter began giving private readings of the play in the homes of friends, including one at the home of television producer Norman Lear. Academy Award-winning actress Shirley MacLaine was among the guests.

“She believed (physicist and cosmologist) Stephen Hawking was the reincarnation of Sir Isaac Newton and suggested I add Newton to the mix,” Carter recalled. He turned down the suggestion. He needed to stop somewhere, he told MacLaine, or else the play would never be finished.

Carter consumed all the information he could find about these men. He has a massive floor to ceiling bookcase in his home filled with books only by and about Jefferson, Tolstoy and Dickens.

Roughly 60 percent of the dialogue in “Discord” is directly from other writings by these men — journals, diaries, compendiums.

Carter and Borgia have known each other since they met in 1987 at Dixon Place, an experimental theater in New York where Carter was doing standup comedy and Borgia designed sound and music for two of Carter’s monologues, which they performed at small off- and off-off Broadway theaters.

“Our offstage conversations had a thread of belief,” Borgia said via email. “Scott had just begun a personal program of answering the door when Jehovah’s Witnesses would knock and invite them in to hear what they had to say. He would listen, thank them, and they would depart. I think he just wanted to get their take on it. I didn’t know you could do that.

“He wasn’t afraid of other people’s beliefs, which was refreshing. A prevalent feeling in my circles was that religion was simply stupid and ignorant, which didn’t square with my experience though I was pretty much an atheist myself.”

Borgia has been working with Bridge Street Theatre since March as an associate director with founding directors John Sowle and Steven Patterson.

“‘Discord’ is a perfect fit for the theater in terms of theme and scale,” Borgia said. “I hadn’t seen a production of the show, but I’ve seen Scott do a couple of readings, which made an impression.”

Borgia’s interest in directing “Discord” stems from his own interest in “the role of faith in our current world. I like watching respected historical figures suffer,” he said. “Makes my brain work in a good way.”

The directorial challenges are formidable. “It never stops,” Borgia said; “three actors on a stage from the first scene with no bathroom breaks. … There is a lot of historical and character background written into the script that must feel natural when performed; that requires a load of finesse from the actors, which they all possess in quantity.”

Borgia characterizes Carter’s script as “a beautiful puzzle, most of the answers are right there in the text. … The characters fight about their beliefs which allows the audience to share beliefs with one another.

“(We’re) not out to convert anybody,” Borgia said; “discussion leads to better understanding.”